GFJ Commentary

June 21, 2021

After a successful start of the new Commission,

the EU in troubled waters

By Karel LANNOO

The EU is experiencing big challenges on many front: the ongoing response to the Covid crisis, the further completion of the single market, above all on the digital front, the digestion of Brexit, and framing its external relations in between the US, China and Russia, and rest of the World. While the initial response to the Covid crisis has been fast and very pronounced, it is struggling now on an unknown territory, healthcare and the relations with the pharma industry. The EU is also fighting on the external front to be respected as a partner, with the additional difficulty to find consensus on foreign affairs matters among its own members.

The Von der Leyen Commission, the 27-member College in charge of the day-to-day management of the EU, started a bit more than a year ago as the geo-political Commission. It is a political Commission, with representatives of the three large political groups in the Commission College, following the structure of the previous Juncker Commission, with the President and the five vice- presidents, including the high representative for external affairs, dealing with the overall direction. The big themes on which the Commission started are digital and strategic autonomy, and the Green New Deal, but this was overshadowed by the Covid crisis, which continues to be the main priority until today, more than one year after the crisis started.

This article discusses the big themes on the EUs agenda today. On the internal front, it examines the the Covid budgetary and the EU’s health policy response. On the external front, there is the multiplication of the trade deals, to start with the UK, but the more general question, whether it is squeezed in between the US and China.

The Covid economic and budgetary response

Notwithstanding initial inertia and national reflexes, Europe has managed to react rapidly to this crisis, thanks to an effective combined leadership between the EU institutions and the capitals. The quick response by the ECB in March with the Pandemic purchase programme, followed by the Eurogroup in April 2020 with the agreement on special credit lines from the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), the radically upgraded EU budget have changed the paradigm. The EU should now take this logic forward, also on the international scene.

Whereas in February 2020 EU leaders were, just before the Covid crisis started, arguing about a few digits for the new EU budget for the period 2021-27, the new budget doubles its size to over 2% of EU Gross National Income (GNI). Given the unprecedented economic situation, the member states allowed the EU Commission to borrow directly on the markets, following Art 122 of the EU Treaty, and by this make an exception to the EU’s own resources rules. This legal basis was first used for the SURE (Support to mitigate Unemployment Risks in an Emergency) regulation in May 2020, which allowed the EU to raise €100 billion to bolster national unemployment schemes. This is a huge step forward in further ‘europeanisation’ of policies, affecting labour markets, SME financing, healthcare and related research, all of them almost fully national today, but also resetting cohesion policy and reinforcing the green transition.

For the main budget, the Next Generation EU adds €750 bn to the €1,074bn of the MFF (the EU’s Multiannual Financial Framework), with a borrowing by the EU on capital markets of, to be reimbursed over a very long time. This will be a big step towards a more integrated bond, and European capital markets. With the EU Commission’s AAA rating, it will for the first time create a truly European safe asset for institutional investors, like a US federal Treasury bills, and a single yield curve for the markets. Together with the €500 billion of outstanding borrowing from the European Investment Bank (EIB), the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) and other entities, this makes at least €1.4 trillion in triple-A truly European assets. At the same time, it will strengthen the international role of the euro, which had declined the last years, to the benefit of the dollar, and the US, and affecting Europe’s position globally, like in trade with Iran.

As this borrowing is not supported by the current revenues, it will unleash another dynamic towards creating a truly own resource or revenue for the EU. Several ideas have already been raised in this direction, but the most likely seems a share of the corporate tax revenues of the member states. This can however only be done on the basis of a much higher degree of tax harmonization, another until recently distant dream, and an area where the EU today hardly has a single market.

Through this reinvigorated budget, the EU’s funds will have a much bigger impact on member states spending, which was on issue of tight discussion until an agreement was concluded in the European Council of 11 December 2020. More in particular, the discussions centred around the conditionality the EU Commission can impose on the member states for getting EU funds. The conservative and populist governments of Hungary and Poland, which are already for some time had been a source of concern for the EU Commission with regard to the application of the EU’s rule of law principles with regard to the existence of free media, the separation of powers and migration policy, resisted any conditionality. The agreement reached states that breaches of the principle of the rule of law do not only apply when EU funds are misused directly, such as cases of corruption or fraud, when the EU’s financial interests are at stake, but it also applies to systemic breaches of fundamental values that all member states must respect, such as democracy or the independence of the judiciary, when those breaches affect – or risk affecting – the management of EU funds.

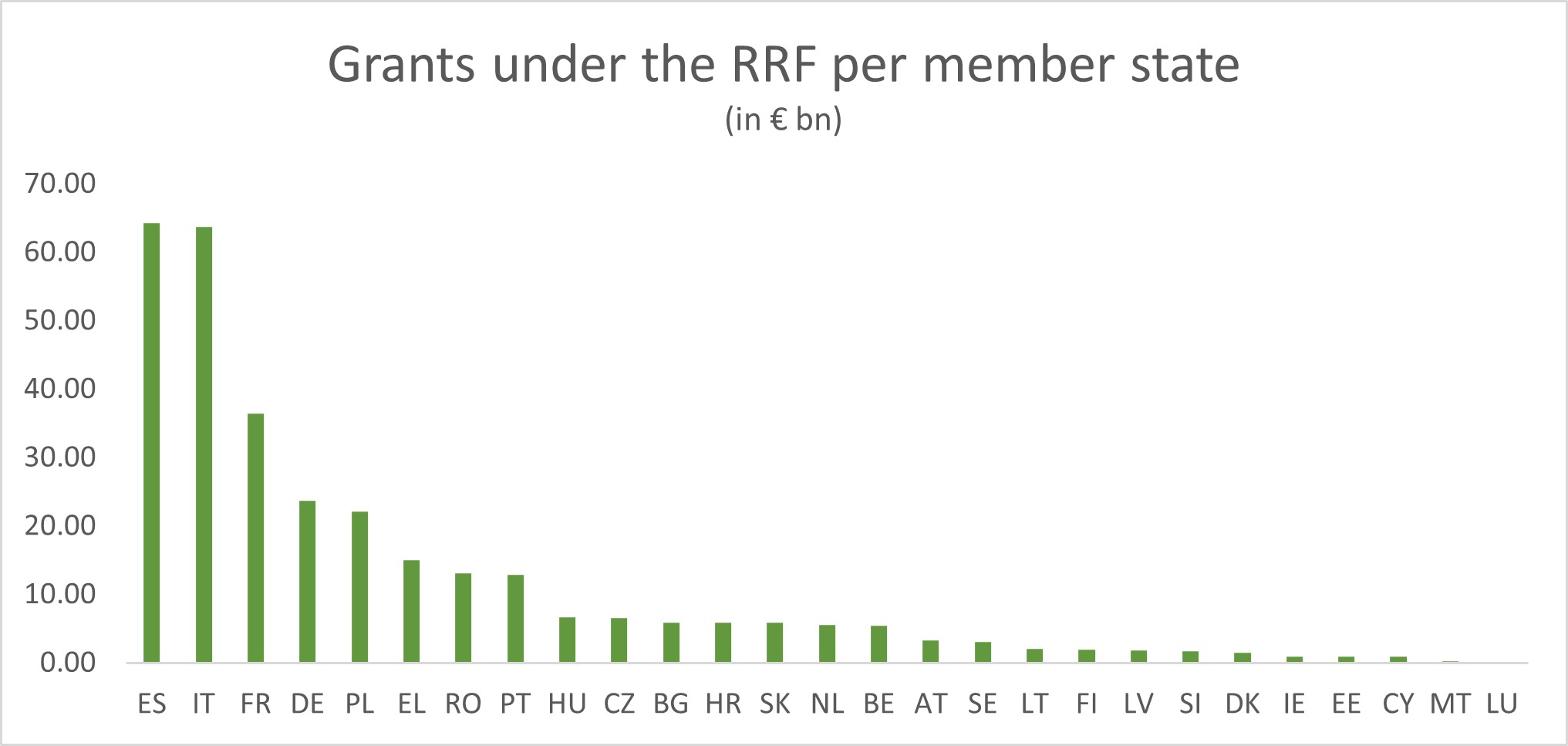

For some countries, the funds available through these lines will be enormous, and add considerable to national budgets. According to EU Commission calculations, the entire Next Generation EU package could raise real GDP levels by around 2% by 2024 on average, in addition to the transfers that are already happening under the structural programmes, that are very important for the central and Eastern European countries of the EU. But questions have been raised regarding the absorption capacity of the governments of these funds, and the need for additional fixed capital formation, as compared to other investments. Politically, it also provides for a ground for bickering among political parties on spending plans. Discussions in Italy, the largest beneficiary with Spain of these funds in volume terms, on the allocation of the funds, led to the demise of the Conte government and the formation of a new government with Mario Draghi, former President of the European Central Bank, as prime minister. The chart below shows the beneficiaries of the grants (as compared to loans) in total value under the Recovery and Resolution Facility (RRF) of the MFF.

The EU4Health

The EU reacted rapidly as well on the core health care front, but the response got entirely blurred in disagreements among member states on the role of the EU in this domain, with pharmaceutical companies on delivery targets, and with the public opinion on the dismal performance of member states health administrations. It is too early to predict the outcome at this stage, but it is clear that the EU lost a lot of credibility, possibly as a result of over-reach.

On 17 June 2020, about 3 months in the Covid crisis, the EU Commission published its vaccine strategy, with joint procurement through Advance Purchase Agreements (APAs). The first procurement was placed already in August 2020 with a large pharmaceutical company followed by several others in the following months. The procurement process is run by the Commission on behalf of all participating Member States, with a budget of €2.7 bn. But the liability for the deployment and use of the vaccine remains with the purchasing Member States.

In the context of its industrial strategy, the EU Commission reacted with a pharma sector strategy, composed of initiatives to support a competitive and resilient industry in the EU. It proposes ‘to identify strategic dependencies in health, and to propose measures to reduce them, by diversifying production and supply chains, ensuring strategic stockpiling, as well as fostering production and investment in Europe.’ It notes that authorities do not know the strategic supply chains in pharma, that vulnerabilities should be identified and security of supply of medicines be ensured. Proposals for legislation are announced, which are also encompassing the quality of and sustainability of the production process.

As part of this strategy the EU Commission also announced an upgraded and expanded institutional structure in the domain of healthcare policy, with the creation of a European Health Emergency Response Authority (HERA, or a European BARDA modelled on the US federal Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority) as crisis response infrastructure and agent for strategic investments for research, development, manufacturing, deployment, distribution of medical countermeasures, with a proposal expected by end-2021. A HERA incubator should develop a bio-defence preparedness plan in the form of a public private partnership. It also proposed the European Medecines agency (EMA) and the European Centre for Disease Control (ECDC) should be upgraded.

The problem with this strategy is that healthcare is a state or local competence, not a federal responsibility in the EU. The EU has however been active in the pharmaceutical sector with rules regarding products that can be sold in the single market and in trade with third countries, the protection of intellectual property, the promotion of R&D and the preservation of competition. A large body of legislation regarding pharmaceutical products exists with the progressive harmonisation of requirements for the granting of marketing authorisation and post-marketing monitoring by the centralized European Medicines Agency (EMA) or by the member states, and recognized mutually. But on the level of prices, there is not really a single market, as there is no single price, certainly for prescribed drugs, as prices are set by the states.

Creating new or upgrading existing federal agencies requires budget and real competences. The Stockholm-based ECDC, which has an annual budget of €59 million and a total staff of about 270 persons (2019), was constantly behind the curve in the beginning of the pandemic. Like the CDC of Dr Fauci in the US, it is the official “EU agency aimed at strengthening Europe’s defences against infectious diseases”, but it hardly gave any advance warning of the impending catastrophe. The Commission, which oversees the ECDC, was as well constantly behind the curve on the threat of the pandemic, and the implications it could have on EU economies and EU freedoms. Until today, the ECDC is not known among European citizens, unlike the CDC in the US. Hence it would be important to ensure that existing institutes can function well, before new ones are created. This may imply clear competences in the domain of health for the EU.

Until today, the vaccines strategy has remained in the middle of the attention, with delivery delays, tensions between the EU Commission and the pharmaceutical companies, but also between the EU Commission and the member states, and between the EU and other countries, mainly the UK, with threats for export bans. The delays in the vaccination in the EU as compared to the UK and the US can be expected to have long lasting effects on European policy making for years to come, but it is too early to say now in which direction this will go. We would not advocate an overall expansion of the EU’s competences in healthcare, but plead for a very targeted change, to ensure that the certain tasks can be properly or better observed by the exiting agencies.

The EU’s new relations with the UK

After the Brexit vote in June 2016, the EU’s new relationship with the UK took four and a half years to be structured in the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA), that was concluded on 24 December 2020. Overall, the agreement was welcomed as it sets zero tariff goods and specific rules for services trade, a governance structure with a Partnership Council and specialised committees, a mechanism for dispute settlement and cooperation in a variety of fields, as might be expected for a former member and close neighbour. The most difficult parts concern those regarding the level playing field for subsidies (or state aids) and environmental, social and tax matters, as further to the EU-UK Withdrawal Agreement of November 2019. However, as compared to the EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement, concluded in 2019, and other trade agreements such as with Canada (CETA) and the Eastern European neighbours (the Deep and Comprehensive Trade Agreements, DCFTAs)), it does not, or only to a very limited degree, aim to advance political cooperation, although this will be needed already alone for Europe’s security.

For goods, the TCA is not a customs union, even if there are no tariffs. This means that goods are checked on the borders for conformity with national rules, which has delayed trade between the EU and the UK since January 1st. In effect, trade between the EU and the UK has declined importantly, as was to be expected. Some see this a temporary, as agents need to adjust to the new measures, but others expect this to become more permanent, as was predicted in most Brexit impact studies.

For services, it is too early to have a clear view, but on those most important for the UK, the financial services, there has been a direct shift of EU equity trading to mainland Europe since 1 January 2021 because of regulatory reasons. This was widely reported in the media, but however is only a very limited slice of all the activities taking place in the City of London. The most apparent lacuna of the TCA was the lack of a dedicated financial services committee. The agreement has a dedicated chapter on cross-border financial services and investment under the TCA, following the (most favoured) national treatment and anti-discrimination rules (Section 5.37 of the TCA). But it provides for a prudential carve-out, as in other international trade agreements, which allows each party to adopt or maintain measures deemed necessary for consumer and investor protection or the stability of its financial system.

The most important parts of the TCA, and unique sections for a trade agreement, regard the level playing field (LPF), which was most likely what caused most problems in the negotiations. If there are significant divergences (e.g. on labour and social regulations, environment and climate, taxation) that could have a material impact on trade or investment between the EU and UK, rebalancing measures may be introduced to address the distortions, with a dispute settlement system, and an arbitration panel as last resort. The same applies for subsidies or state aids, where remedial measures could be requested.

Like with other trade agreements, it will take time to have the TCA properly implemented. The additional problem here is that it concerns for the first time an agreement with a former member of the EU, meaning with lesser freedoms than the operators and citizens in country in question were used to before. This is currently creating tensions between both, more specifically in the context of the availability of vaccines, and the huge difference in the performance of administrations on both sides. On that level, ‘taking back control’ has apparently worked on the UK side, to the discomfort of the EU countries, and the EU Commission in particular.

And the new relations with Biden’s US

The presidency of Joe Biden heralds an opportunity for Europe, and more particularly the EU, to revive its relationship with the US. But it may also be its last chance. The EU will have to demonstrate tangible progress in the areas of defence, trade and global policy stances generally to ensure the good will of the new American administration.

After very strained EU-US relations over the past four years, the election of Biden and his early statements have produced a huge sigh of relief among many policymakers in the EU, and Europeans at large. The stances of President Trump and his closest advisers were unprecedented in the history of transatlantic relations: from the open attacks on the EU and some of its leaders, to support for extreme-right Eurosceptic parties and governments, and threats and attacks on the security and trade front.

To some degree, the Trump administration was only pointing to issues others had already raised tacitly before: the asymmetries on many levels in the transatlantic relationship had to end. Europe has sheltered for too long under the security umbrella of the US, and not taken enough responsibilities of its own. Despite warnings that date back to the end of the G.W. Bush administration (2000-2008), defence budgets have hardly increased. On the goods trade side, where the EU has a huge surplus of more than €150 bn (2019), the US often applies lower tariffs on EU imports than vice versa. The obvious example is the most important EU export product, cars, where the US places a 2.5% tariff on EU vehicles, while the EU applies a 10% on US ones. This has insulated the EU market from competition, which is why it is behind others on electric cars, for example.

The US security umbrella has already folded in Europe’s south-eastern neighbourhood, and will not reopen, nor has it been replaced by European security. Notwithstanding the calls for a geopolitical Commission, Europe has been absent while Russia, and in the second instance Turkey, is becoming the hegemon in the region. As Russia brokered deals in Armenia, Syria (Idlib) and Libya, and extended its influence, Europe was nowhere to be seen. The void left by the retreat of the US has been filled by a former Cold War enemy.

Europe’s precarious security situation became apparent under Trump; without NATO it has no real actionable security or crisis intervention structure, and is thus very vulnerable without the US. Most recently, EU plans for a more advanced security cooperation (PESCO), started under the previous legislature, have been overshadowed by uncertain proposals to include the UK’s defence capacity in a structure above the EU, in a European security Council. In the meantime, taken collectively, European member states that are allies of NATO do not meet the 2% defense spending as a percentage of GDP objective set by NATO, but stick on average to around 1.6%. This means that Europe lacks core operational capacities, such as the air transport capacity to move troops to crisis-hit regions, for example. EU countries should agree urgently on a division of competences and local specialisation, as part of a European defence agenda, as the Dutch Council for International Affairs argued in its recent report. The EU will only be taken seriously by the US – and also by President Biden – if it takes on more tasks itself.

On the trade front, it will take a long time to re-establish EU-US cooperation to the level where Obama left it. Biden has not yet mentioned TTIP as one of the engagements he would restore, although he will allow the WTO to function again. In the meantime, the EU has advanced with important bilateral trade deals, while a specific trade agreement on investments (China Investment Agreement, CIA) was concluded with China on 30 December (which also the US did two years earlier, as was highlighted in this piece, even if the US indicated not to appreciate this agreement. The former US Trade Representative, Robert Lighthizer, saw this web of bilateral trade deals as the resurrection of “the system of colonial preferences that prevailed in the pre-GATT era”. These deals do not advance liberalisation, he argued, but force countries to adopt protectionist measures such as ‘geographic indications’. WTO member states should therefore recommit to market reform and most-favoured-nation status, he advised in a piece in the WSJ in September. This is what Biden has already announced, to remove Trump’s tariffs and bring the WTO back to the centre, which the EU should be fully take into account.

Looking at it from an economic standpoint, the incoming administration may take a pragmatic approach: it will restore good old relations with Europe, but will turn to where the gravity is shifting: Asia. In the share of the global GDP weighting, the EU continues to lose ground, the US remains in the lead, while China is advancing. These trends are accelerated by the Covid-19 crisis, which has highlighted our dependence on US big tech. This puts Europe in a dire position with its digital tax, where the only solution is a global one for effective taxation in the realm of the OECD. The EU will thus need to watch out in the coming weeks and months that it fulfils its side of the bargain in relations with the US perform on its side of the relationship with the US, making genuine commitments on the security and defence side, also by advocating a truly open trade agenda in line with the WTO commitments, to boost its competitiveness.

Conclusions: a challenging 2021

The EU thus got of on a very challenging 2021, or second year of the Vonder Leyen Commission, with major assignments on many fronts: the ongoing health crisis and the availability of vaccines, the fiscal response to the crisis and the respect of the EU’s rule of law, the management of its relations with its former member the United Kingdom, and the response to the demands of the incoming Biden administration on the trade, security and digital front.

Apart from that, there are many ongoing policy priorities, with on the internal front the digital agenda, and the response to the dominance of US, and soon, Chinese, big tech in the EU’s internal digital market. There is the Green Deal, and the goal to be carbon neutral by 2050. Carbon emissions with 55% should already be reduced by 2030, with huge implications for adjustment in energy markets, transport, housing and industry. This also raises problems for the modalities of trade with countries that do not respect these targets.

The Covid crisis can be expected to be under control by the middle of this year, but the implications will impact economies and the public opinion for years to come. For the EU it means more responsibility in the coordination of health care policies of the member states, and in bio-medical research. On the fiscal front, the EU has been successful in making much more support available for the member states from its own budget, but it will need to ensure efficient and future oriented spending by the member states.

On the external front, the relations with the UK will remain strained for some time to come, but can be expected to normalise, as both sides have all interests in stability. With the Biden administration, the EU, and Europe overall, will need to ensure to take more responsibility for its security. The EU will also need to facilitate the trade relationship, which was so tense during the past four years, with some unilateral overtures. But the most difficult relationship is with Russia, which will remain unpredictable, and thus dangerous, for long.